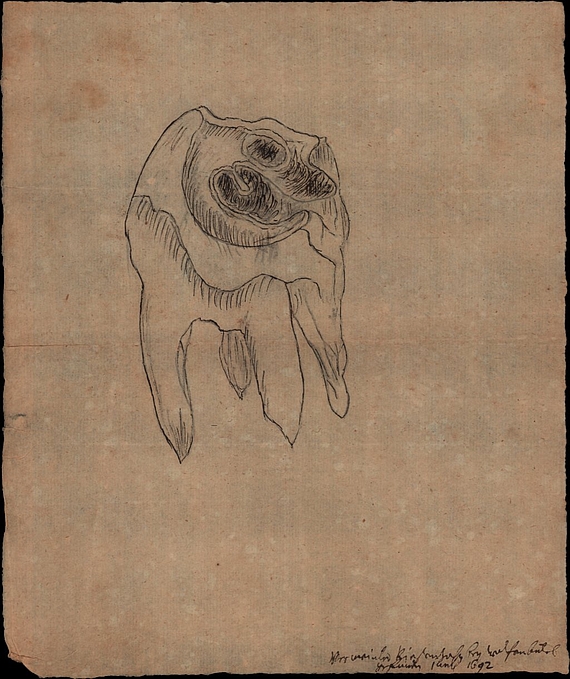

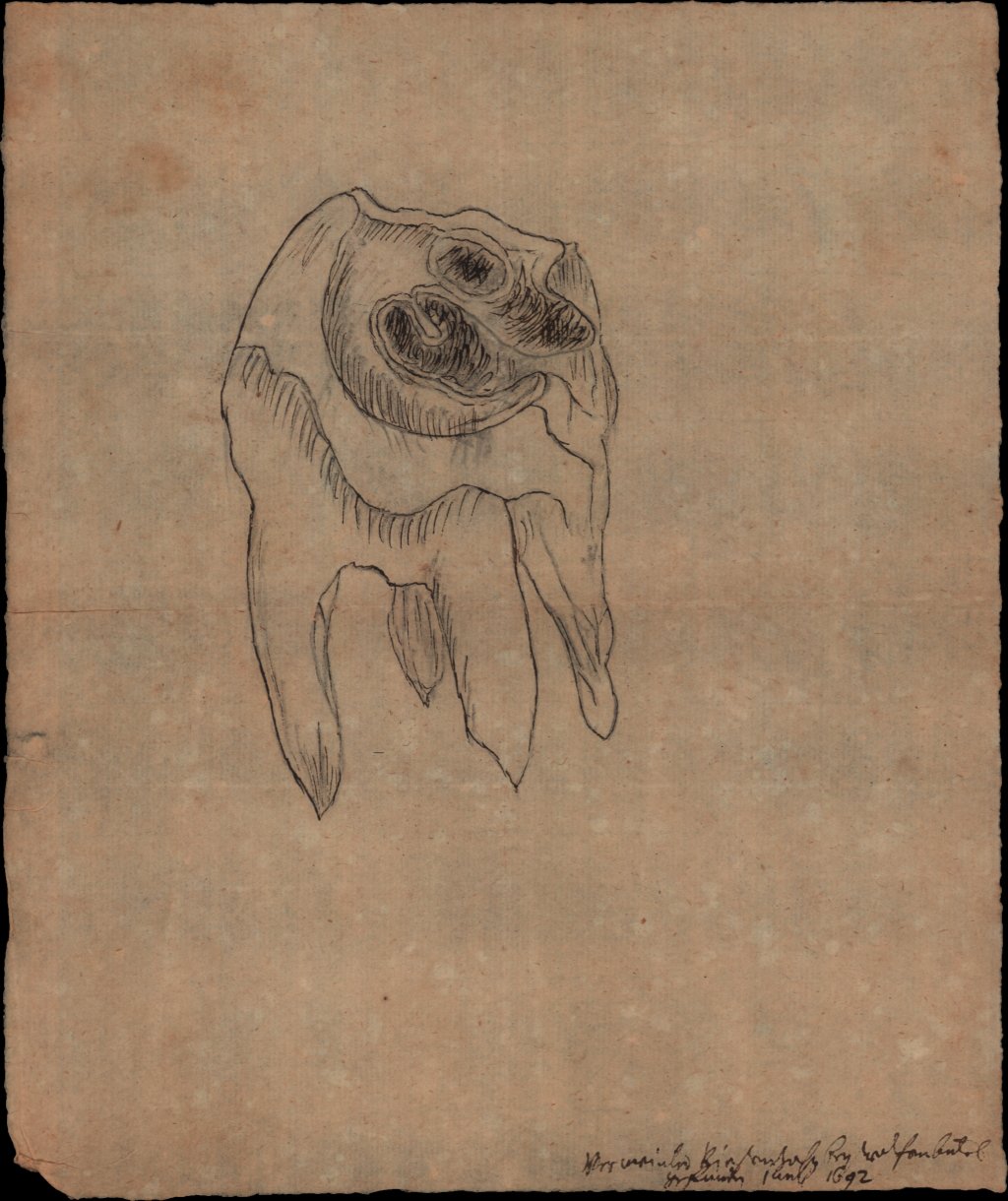

While staying in Hannover in June 1697, court counsellor Leibniz received a parcel from Wolfenbüttel. It contained a strange, gigantic tooth. In addition to the enclosed scale drawing, a letter explained that Leibniz’s expertise was required in the context of “the discovery of a human skeleton of a horrendous size”. On the corner of the page, Leibniz added the following note: “Alleged giant’s tooth found near Wolfenbüttel in June 1692”. From Hannover, he wrote to Electress Sophia, who resided in Herrenhausen: “I have just been sent the rather large tooth of an unusual animal, whose skeleton has been found near Brunswick, and have been asked to share my views on the matter. Most are adamant in their belief that it is a giant’s tooth.” Leibniz did not believe in fairy tales and argued that if it belonged to a giant, “it would have been as tall as a house”.

At the time, many phenomena could not be explained. Apart from superstition, the Bible was often consulted to interpret mysterious discoveries or processes related to the history of the Earth. Even the age of the Earth was determined by referring to information from the Old Testament: The Irish bishop Ussher (1650) established the 23rd of October 4004 BC around 9 a.m. as the date of the Creation. Based on astronomical calculations, Isaac Newton post-dated the Ussher chronology by 534 years. Little did he know that he misjudged the date by approximately 4,542,994,880 billion years. Leibniz followed a more solid approach. In order to interpret the age of the Earth, he intended to consult the ‘witnesses’ of nature instead of relying on documents produced by humans.

During his frequent travels in the Harz Mountains, where he attempted to improve silver mining in the Upper Harz region through innovative inventions, Leibniz became increasingly interested in geoscience. He visited local caves and compiled a collection of rocks and fossils presumably comprising about 100 pieces. This gave him the idea to add a preface to the history of the House of Brunswick containing nothing less but details on the universal historical processes in the prehistoric and protohistoric region of Brunswick-Lüneburg. He started to work on his book about the primordial Earth, titled Protogaea. In particular, Leibniz was fascinated by fish imprints preserved in copper slate near Osterode. Back then, most people considered such images hidden in stone to be “ludus naturae”, whims of nature left behind by a Maker, who “has imitated teeth and bones of animals, mussels and snakes for our amusement”. Leibniz saw a striking resemblance between those imprints and today’s species and found that they frequently occurred in parallel layers. He realised that the fossils were “remains of animals” whose former bodies were destroyed long ago but “were filled with a metallic substance”. Just like the majority of his contemporaries, Leibniz did not question that God once sent the Deluge. According to the Book of Genesis, the water prevailed 15 cubits upward above all mountains. Although he considered some ideas regarding the origins of life quite conclusive: “In their arbitrary speculations, some believe that creatures that now live on land have once been aquatic animals during a time when the ocean covered everything. When this element retreated, they gradually turned into amphibians, while their descendants grew unaccustomed to their original habitat” Leibniz did not dare to challenge the Bible’s authority: “This contradicts the Holy Scriptures, and deviating from them is sinful.” Leibniz realised that the ‘giant’s tooth’ bore a great likeness to elephant molars, that are “covered with furrows and indentations just like mill stones, which they use for crushing their food into a mass similar to flour by grinding it between their teeth. And this tooth has furrows just like that”. However, referring to the Deluge paradigm, Leibniz concluded that it must be part of the remains of sea creatures: “Since there are walruses or manatees in the Arctic Ocean that resemble elephants in certain aspects”.

Today, we know that the ‘giant’s tooth’ is the upper left molar of an enormous woolly rhinoceros, that lived in Wolfenbüttel during the Ice Age. Which is just as fascinating as imagining a giant. In his Protogaea, Leibniz concluded: “For us, nature thus takes the place of history. In exchange, our written accounts repay nature’s mercy, so that her glorious creations, which we can still see with our own eyes, may not be lost to those who come after us.”